On or off the balance sheet? The EPEC pushes for clarity on PPPs

Posted 27/01/2020 by Nuno Sousa

There’s no avoiding it: building good infrastructure costs money. Whatever value such projects can – and do – provide in the long run, governments seeking to refresh or extend their infrastructure must sooner or later find the funds to pay. But, for the cash-strapped, there are options…

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are one such opportunity. They’re designed to enable the private sector to help reduce the costs and risks that come with large-scale infrastructure projects. PPPs are used the world over but are particularly popular in Europe, where government spending is limited by the Maastricht Criteria – a set of rules created to prevent government deficit and debt surpassing a certain percentage of GDP.

PPPs have been making infrastructure possible for some years, but it isn’t all plain sailing. The financing of large-scale projects is constantly under review to ensure that governments, private investors, and the end-users of infrastructure are all getting the best deal possible. Under the spotlight today is statistical treatment.

Understanding statistical treatment

Not all PPPs are born equal. PPPs fall into two categories of “statistical treatment”: either on or off the balance sheet of governments. This is no small detail. It can mean the difference between infrastructure projects succeeding and failing. Such examples are easy to find:

BELGIUM TO RETENDER EUR 385M TRAM OVER EUROSTAT VETO

“The EUR 385m Liège tram PPP is to be retendered after being rejected three times for an off-balance sheet classification from Eurotat, the government said on Friday (25 March) in a statement.”

SCOTLAND SCRAPS SMALL-SCALE DBFMS

“Scotland has scrapped the DBFM model for future smaller scale “hub” schemes, leaving deals due to be privately funded being switched to a design build model at the last minute. The move, which is said by sources to have disappointed the likes of Equitix and INPP that have invested in hub schemes since their formation nine years ago, follows a decision by Eurostat that hub schemes to be reclassified as on-balance sheet.”

MAJOR POLISH EXPRESSWAYS PPP MAY FACE EUROSTAT HURDLE

“Procurement could be pushed back depending on the Eurostat outcome. Under Eurostat’s System of Accounting 2010 (ESA10) public debt accounting regulations, the rules regarding clear allocation of financial risk between public and private sectors – hence whether a project was defined as off the government’s balance-sheet – were changed.”

WELSH PPP SCHEME PASSES EUROSTAT TEST

“The European Union statistics agency Eurostat has confirmed that a new Welsh PPP model will not result in the projects having to go on the government balance sheet.”

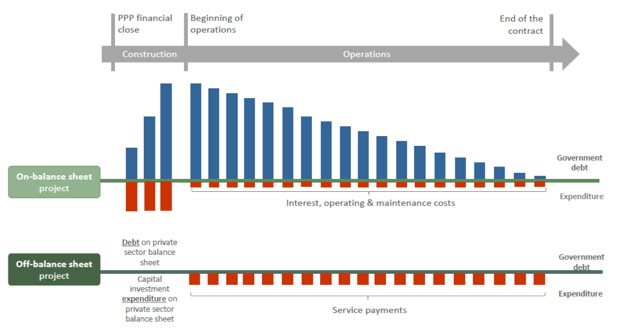

The key differences

If an asset is recorded as “on balance sheet”, this generates an immediate impact on the country’s deficit, due to the capital investments made and recorded over the construction period. It will also impact the country’s level of debt, due to the liabilities incurred to finance the PPP. It’s easy to see how this could cause problems for those in danger of falling short of the Maastricht Criteria.

Conversely, assets deemed to be “off balance sheet” have a deferred impact on deficit figures, with regular payments for services instead being recorded over the long-term. Clearly, this offers a level of motivation for countries to go “off balance sheet” in a bid to ease pressure on national finances.

It’s no surprise that an increasing number of countries are opting for PPPs, using the off balance sheet treatment to make invest possible. And this trend hasn’t gone unnoticed.

The EPEC (European PPP Expertise Centre) has raised a flag relating to statistical treatment. They suggest that there’s a tendency in certain European countries to opt for PPPs simply due to the opportunity to go off-balance. While we’ve seen the benefits of doing so, this approach isn’t without its downsides.

An excessive focus on statistical treatment

Putting too strong a focus on the “off balance sheet” statistical treatment can cause problems. Ultimately the belief is that it’s leading governments to opt for public-private partnerships for projects that aren’t suitable.

In some cases, there may be little value in bringing the private sector on-board. Other times, a project may simply offer poor value for money through PPP. We’re also seeing the emergence of bankability issues, and the mismanagement of fiscal liabilities.

But perhaps the most significant danger is the affordability illusion. Independent of a project’s statistical treatment, PPPs represent long-term financial commitments, which will eventually – inevitably – impact a government’s budget.

In short, the public sector is sometimes opting for PPPs where it is not justified and may not make good sense. The EPEC has teamed up with Eurostat – the body responsible for creating the rules for statistical treatment – to find ways to change that.

A push for clarity

In a bid to clear things up, Eurostat and EPEC have created a practitioners’ guide. The guide – which is available online – intends to improve understanding of how Eurostat’s rules on PPPs are put into practice.

Eurostat’s rules comprise the system for determining statistical treatment of PPP projects. Their methodology is based on three steps:

- (i) Identifying the provisions of the PPP contract that influence the statistical treatment.

- (ii) Analysing the degree to which each of the influential provisions has an economic impact on the projects.

- (iii) Concluding the statistical treatment assessment which includes, but is not limited to, the use of a quantitative/scoring approach

The initiative is aimed at public sector stakeholders, but there will also be value for the private sector. To make life easier, the guide uses the structure of a typical PPP contract, with which readers will already be familiar.

The guide’s ultimate objective is to help make PPPs a reality, and ensure they are implemented in the right way. It’s hoped readers will take away a greater understanding of the impact projects can have on government finances from the beginning – before the procurement process is underway. Eliminating this potential detriment is essential for both public and private parties – from PPP stakeholders to those making use of infrastructure on a daily basis.

And the benefits aren’t merely financial. The hope is for better infrastructure, via a meaningful reduction in the number of delays, suspensions, and cancellation affecting projects everywhere.